Tool: The Master Study

Today we are going to steal a tool from the visual artist’s cabinets and see if we can bang it into shape that works for writers. It’s called a Master’s Study, and it’s part copying, part analysis, and all hands-on learning.

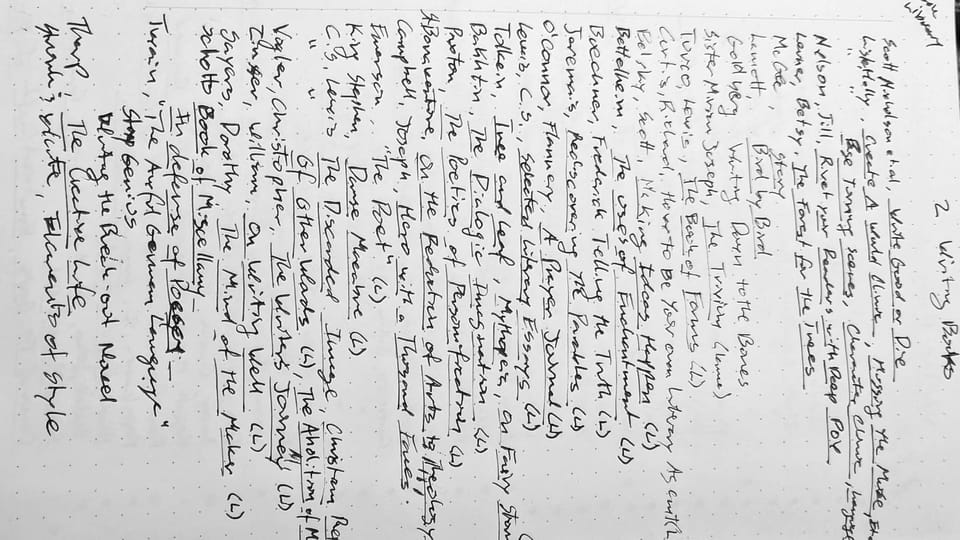

Welcome to Tools, the other half of writing about writing about writing. This tool is a long one, and doesn't pertain to a specific book. But its one I use frequently and will reference in upcoming posts so I figured I'd put it up here early so you all have access to it too.

Have you ever read something and gone “How the F*ck did they do that?” Maybe it was a story twist. Or a single perfect sentence. Either way it cued up a wave of existential despair: How do you even learn to do that?

Well today we are going to steal a tool from the visual artist’s cabinets and see if we can bang it into shape that works for writers. It’s called a Master’s Study, and it’s part copying, part analysis, and all hands-on learning.

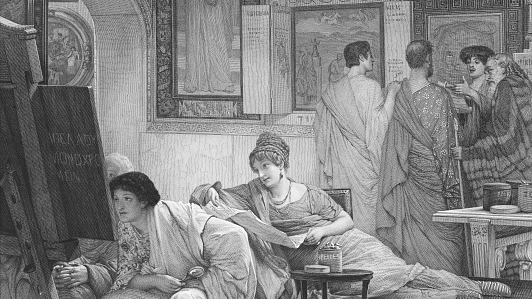

Weekday mornings in art museums belong to the artists. These folks are first in the door and have to be kicked out at the end of the day. They’re there to work and give you the barest nod before pulling out pad and pencils, or if they’re lucky and the museum allows it (usually only at reserved times), oils and canvas. And while it looks like they are simply making copies of the artwork, more often they are there to learn a specific skill in the only real way an artist can, by doing it with their own hands.

What does this have to do with writing? A master study, the formal art-school term for these copies, involves closely observing the work and then attempting to duplicate first the work, and then the effect the student is trying to learn. It’s about skills acquisition when there’s nobody who can tell you how it was done, and telling you wouldn’t teach you what you need to know anyhow, you’ve got to be able to do it yourself. Sound familiar? It’s a method of speed running a new skill using close observation of works known to have the qualities you want to acquire.

Quick note: This ideally would take you several days and is inherently a time-intensive process. If you don’t feel like you have the time, picking any one step for ten minutes is OK too.

Method:

0. Identify a skill you’d like to acquire

An artist might say “I want to be able to paint light shining through the surface of water.” A writer might say “I want to be able to describe a character with sharp and telling details.”

Knowing what you need to learn is either the simplest or the hardest part of this process. If you’re not sure what skills you are lacking, move to the next step with an example work by a writer you admire deeply. Your taste is still killer, even if you’re not measuring up to it yet. We’re here to begin to close that gap.

1. Pick an exemplar

Pick a single piece of work that you are going to closely observe and then copy. If you are building a skill, this should be an excellent example of the skill you’d want to learn. It should also be a piece you like a lot, because you’re going to spend a lot of time with it. If you are not building a specific skill, pick a piece that is most like what you would like to produce yourself. There’s something there that you deeply admire, even if you’re not entirely sure what it is. Your exploration of the work should help you identify the qualities you admire and want to acquire.

For writers, I’d suggest picking one page to four or five (print) of a favorite work. Something you can photocopy or print out. Make sure it contains whatever you’re trying to learn about if you have a specific thing in mind. If you want to learn how the author does dialogue, don’t pick a page that doesn’t have any. Ideally the part of the work you admire the most and most want to learn about.

2. Observe the work for an extended period

So this is surprisingly hard. Usually when we read we are only looking at any one sentence for a few seconds. Maybe a few minutes per page. But you need to spend a lot of time, deeply looking at this work. In art classes our teachers recommended spending at least an hour looking at the work, and at least ten of those without making any notes at all. Not drawing, not describing, just looking. I can not understate how hard this is the first time you do it. You get bored, your mind wanders, you reconsider every decision you’ve ever made that gets you to this point in your life. And then you get curious. How did they do that? This is the right mindset. You start noticing things you’d never seen before. The way that a tiny petal on the table is composed of basically only three brush strokes. Or the way a sculpture’s hands dimple the flesh of the woman he is supporting. This is good, you’re finally looking at the work.

For writers. Start by reading that work aloud. Slowly. Then, make a clean copy by either hand writing or typing the entire section. If you can get a typewriter, so much the better. Anything that forces you to go slowly, word-by-word through the work. I personally do this with a fountain pen, on every other line of a piece of paper so I can make notes in the margins. If the piece you are looking at is short, you might want to copy it several times.

3. Document your observations - write that shit down.

When you’ve finished your copy. Make a few notes about what you observed. What caught your attention? Can you identify how they did the thing yet? No? Time to annotate.

For an artist these first copies result in lots of annotated sketchbook pages and “studies” where you reproduce a portion of the work at lower resolution. You might do a color study where you only paint the broad blocks of colors so you can see how the work’s colors interrelate. And you might do a shade study where you reproduce the areas of light and dark in the work to find how the light works in the piece. And you’ll break down the composition of the piece, or lay out the perspective lines. You might do a pencil sketch that tries to reproduce the direction of the brush strokes. And the *whole time* you are writing down new observations about the piece as you notice more and more. At this point you’re either overconfident or falling into despair.

For writers, now get out the highlighters, colored pens and sticky notes. Photocopy the work if you can (or just write another copy, more time observing). Print the work with lots of room between lines if you can or arm yourself with a plethora of post-its. Now break that sucker down like a buffalo. You might want several photocopies of a single page, and then highlight and write notes on a different aspect of the work on each page. Some areas you might want to observe: description, sentence length (and patterns therein), action-reaction units, dialogue, simile and metaphor, point of view, character’s opinions. Do at least 2 different topics, but if you’ve got the time, do as many different topics you are curious about. Break it down as granularly as possible. Make copious notes.

4. Replicate the work

For an artist this means getting out their tools and finally trying to make a copy of the work. A process that is usually frustrating in the extreme. You discover that you don’t have the manual dexterity to do a certain brushstroke, or your colors aren’t quite right. But you carry on (usually because the damned thing is due in a few hours), and if you’re smart you make notes during this portion too because the parts where you are frustrated are where you need more practice or more drill.

For writers, try to write the section you’ve been annotating from memory, with the piece locked away until you are done. Try to get the wording as close as possible to the original. Which parts stuck? Which parts didn’t?

It will be hard. It is supposed to be hard. There’s research that says that the struggle is what cements information in your mind. That said, you’re not going to produce an exact copy, but you will probably get closer than you expected.

Before you bring the paper back out. Make notes about what parts were easy to replicate, and which parts were hard to remember. Why might that be the case?

Then grab your copy of the work and see how well you did. Where did your word choice differ? Did you forget any parts?

5. Synthesize and incorporate into your own work

For an artist this would be the point where they produce an original work incorporating the learning they’ve acquired.

For the writer it should be the same, write a scene of your own incorporating what you’ve learned in the exercise. Don’t try to write in your exemplar’s style, try to make it your own. What stuck with you? Do you notice any more areas your own work could improve that you weren’t thinking about at the beginning of the exercise?

6. Get critique

This is central to the art school experience. You might present the whole of your research and observations to the class and then do a formal critique of the original works.

For a writer, if you’ve got a critique group, let them know what you were working on and ask them if they think you hit the mark. Can they identify the writer you were referencing? If you don’t have a critique group, you can ask a friend who likes to read to look at it, you can join a writing discord, or use a website like scribophile. Whatever you do, try to get some kind of feedback if you can. But remember this is mostly about self improvement. Do you feel like you’ve improved?

7. Do it again.

By now you’ll have an idea of what this process looks like for you. And likely you’ll be looking more closely at everything you read. It's a self-reinforcing process, the more you learn to observe, the more observant you become and the more you learn from observing.

That’s it. Hope it helps. As always, let me know what you're finding useful in the comments below. Or find this post on Bluesky and comment there.

Resources:

Art:

- Bluesky #Mastercopy - See artists doing the thing. Drop them some encouragement if you've got time.

- James Barrow: How to do Master Studies - Another master study explanation with visual art examples.

Writing

- The Science Behind Productive Struggle - Edutopia on why doing hard things is good for your brain.

- Killer Taste Ira Glass Quote and Audio with interpretation by Krzysztof A. Janczak on YouTube

- Schaubert Family Circus: Best Really Short Stories - a collection of stories under 3K words

- American Short Fiction - Outstanding literary writing mag

- Freesfonline.com - links to spec fiction stories online [currently featuring the Hugo Ballot]

Image Credit: "The Picture Gallery." Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-45609. Image cropped and recolored to black and white.